God's Plan: Mike Holloway's Odyssey from JUCO Hurdler to Olympics Head Coach

Zach Dirlam

10/31/2019

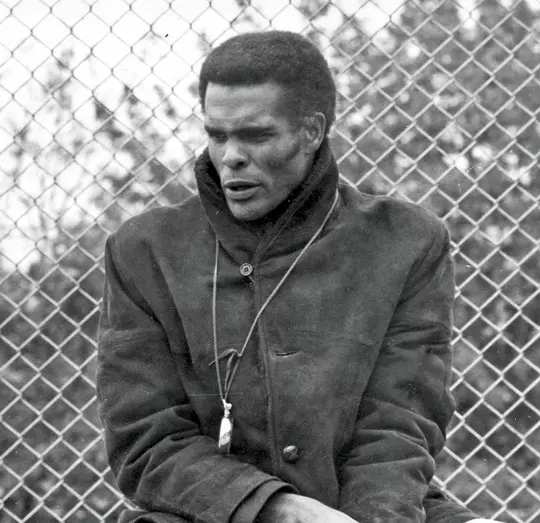

Perched above the backstretch of Percy Beard Track, Mike Holloway’s office overlooks the exact spot where his life changed forever.

At next summer’s 2020 Olympics in Tokyo, he will be head coach of the men’s United States Track and Field team. Accepting that position did not change his life, though. It will certainly be the highest honor in a career full of them. But Holloway was once an unpaid coach chasing a big break, supporting his family with low-paying side jobs. He was a globally-renowned high school coach, then established himself as one of the greatest coaches in collegiate history. He was head coach for Team USA at the 2013 World Championships, an assistant coach for the 2012 Olympics, and his athletes continue to win world titles and Olympic gold medals.

None of those things happen without one moment, 42 years ago.

Behind his desk, Holloway begins telling the story as he gently wheels his chair backward, swivels 150 degrees and looks out a wall-to-wall window, his view obscured by its vertical blinds. He points through an opening, across the infield to the traditional starting line for the 110-meter hurdles, where the grandstands wall bearing a massive Florida Gators logo acts as a backdrop.

It isn’t 2019 anymore. It’s January 1977, and Holloway is a 17-year-old senior from Columbus, Ohio alongside four of his Linden-McKinley High School teammates and coach, Ed Stone.

Linden-McKinley had a talented team, led by Holloway, but Stone knew if they wanted to win a state championship his handful of stars had to sharpen their technical skills. The group traded the frigid Ohio winter for a week of Florida sunshine and intense training, stuffing a high jump pit in the back of Stone’s gutted-out green Dodge van to make the 900-mile drive as comfortable as possible. They played cards and listened to music most of the way. KC and The Sunshine Band composed much of the soundtrack.

“I almost didn’t get to come,” Holloway said. “My mom was like, ‘Ah, I don’t think so.’ Coach Stone convinced my mom and my dad it would be good for me.”

Halfway down the home straight Holloway’s pointing to, Brooks Johnson, a storied coach within the track and field community, watched as Holloway went through a hurdle workout.

Pivoting back to his desk, Holloway rummages through a drawer and retrieves a yellow stopwatch. He coils its rope around his right index and middle fingers, traveling back in time with every spin as he recreates the memory of Johnson correcting a flaw with his trail leg.

“What happens when it gets tighter?” Johnson asked.

“I don’t know,” an awestruck Holloway replied.

“Yes you do,” Johnson retorted. “What happens?”

“It goes faster,” Holloway said.

“Exactly,” said Johnson, then an assistant coach for Florida and head coach for Santa Fe College in Gainesville, Fla. “So if you make your trail leg tighter to your body it will get back on the ground quicker.”

The two discussed technical skills for another half hour. Holloway was completely enthralled by this stern man in a straw hat who dissected the event with the scientific precision of an anatomy and physiology professor.

Shortly after returning to Ohio, Holloway tied the 70-yard high hurdles national high school record. Later that year, Holloway won state titles in the 180-yard low hurdles and 120-yard high hurdles, breaking the state record in the latter event. Linden-McKinley’s 440-yard relay, with Holloway running the third leg, broke the state record (twice) and won the state crown. The Panthers took the team championship home, too.

His future was set. Holloway hitched himself to Johnson, eventually signing with Santa Fe.

Stone, headed there with him, having accepted a spot on Johnson’s coaching staff after losing his teaching job. In August of 1977, they packed everything they owned, couches and all, into Stone’s van, only leaving space for a driver and passenger. They hit the road and drove straight through. A little over 13 hours. The only stops were to switch sides or fill the gas tank.

Gainesville has been Holloway’s home ever since.

“We came here and hung out for a week, then I end up spending the rest of my life here,” said Holloway, returning the stopwatch to its drawer.

“That was an amazing time,” said Eric Taylor, one of his Linden-McKinley teammates. “We still talk about that trip. Once I heard he was a high school coach, then heard he was at the University of Florida, that’s when it all came clear … if it wasn’t for that trip, who knows?”

Holloway leans back in his chair, immersed in blissful memories. To his right, 5-by-8 black and white photos blanket more than half the wall. Every national champion from his two-plus decades coaching at Florida (seven seasons as an assistant, followed by 17 as head coach) is there, as is each ring from the Gators’ nine team national titles. On his left, 19 more 5-by-8s. The backgrounds are black and white but the pictured athletes are in color, popping off the white wall. Those custom prints are for Gators who win medals at the Olympics or World Championships. Immortalization on these walls is a source of pride within the program Holloway built in his image.

As he racked up state title after state title at Gainesville’s Buchholz High School, Holloway dreamt of becoming, as he puts it, a coach of Olympians.

Even as he turned Florida into the powerhouse it is today, producing Olympian after Olympian (he’s coached at least one every cycle since 1996) and living out his dream, Holloway’s aspiration remained the same.

“I wanted to go to the Olympics as an athlete, and when I became a coach I wanted to coach someone who goes to the Olympics,” Holloway says. “That’s always been my goal. I never thought about being the Olympic coach, because I never thought it was a realistic goal or dream.”

***

Melford Boodie still remembers the frustration. Without Holloway, his roommate for the 1978 National Junior College Athletic Association Indoor Championships as a freshman at Santa Fe, Boodie never would have utilized it.

It came over Boodie during a team meeting, the night before the 600-yard dash final. An 18-year-old hothead, it never took much to rile him up. This was different, though.

Coach Johnson addressed the team and gave instructions for each race. Boodie and teammate William Conte were to sweep the 600. Conte, believed to be Santa Fe’s top athlete, would win the title. Boodie would finish second. Hearing that aloud, in front of his teammates no less, stung Boodie. Why should I be satisfied with second? By the time the meeting wrapped, he was fuming.

Holloway pulled him aside. The two were not particularly close. Friendly but quiet was Holloway’s M.O. at the time.

“He doesn’t believe in me,” Boodie seethed.

Holloway knew it was an overreaction, and that Johnson’s spiel had more to do with general expectations than predictions. He also knew Boodie would never understand that fact, nor would he even hear it. Nobody could tell Boodie much of anything. Holloway may not have said much in those days, but he always listened, always observed. Even as a teenager, Holloway was incredibly perceptive, a trait that has come to define his coaching greatness.

“I always knew that he was a student of the game,” Johnson once told an Ohio-based news site.“He always knew what was going on [with] his events and everybody else’s events as well. He was incredibly bright.”

Instead of trying to reason with Boodie, Holloway challenged him. Well, that was how Boodie interpreted it. Exactly like Holloway knew he would.

“Mel, forget that,” Holloway said. “Just kick his ass.”

Those words did the trick. Boodie won the title the following day.

“I needed to hear that from somebody on the team. He coached me to be the best that day. I realized he was a genuine person. If ever there was a problem I had, whether it was personal or not, I could always rely on him to comfort me and show me the way out. Mike is the only person who could talk to me and make me listen.”Melford Boodie

A little over a year later, Boodie needed help. He transferred to Florida State and, for the first time in his life, felt isolated. When Boodie left Washington, D.C., for Santa Fe, several local standouts came with him. Some were friends, others familiar faces. He was the only one to transfer to Florida State in the fall of 1979. Boodie missed his friends and Santa Fe teammates.

Feeling completely out of place and certain he made a mistake, Boodie called Holloway.

“I’m not sure I’m going to make it up here,” Boodie said.

“Don’t worry, man,” Holloway said. “I’ll be up there.”

Holloway fired up his Buick Riviera and headed to Tallahassee, staying nearly a week so Boodie could settle in.

Those stories make it feel as though Holloway was destined to be a coach. He’s always known people. Not in a popularity sense (though today friends and community members jokingly refer to him as the mayor of Gainesville).

He knows people.

Throughout nearly 40 years of coaching, Holloway acquired and developed plenty of unique skills and strategies. The most important one – an innate ability to connect with his athletes and tap into the greatness he identifies within them – was a gift.

At 60 years old but showing no signs of having reached 50, shaping the lives of young men and women, not winning national titles, is why Holloway comes to work every day.

“He loves challenging them.” Stone said. “I’ve watched him get in the face of somebody and tell them, ‘You can do this. Don’t give me any of this you can’t do this stuff.’ He really enjoys having an impact on these kids. And as much as that, having an impact on them personally. That is one of the things he and I talk about consistently – lessons you transfer from athletics into your life, mixing the coaching with the life mentoring.”

***

The old Riviera. That was what Kenny Baylor called it. To this day, Baylor – another one of Holloway’s Santa Fe teammates – Stone, and Holloway laugh just thinking about the 1963 Buick Riviera.

“The love of his life car,” Stone joked.

It was the first car Holloway ever owned. His father sold it to him for $250. Baylor remembers the dark blue paint job and big whitewall tires. Holloway recalls it having a 475 double barrel engine and a speedometer topping out at 180 miles per hour. The transmission eventually went haywire, eliminating the ability to shift into reverse. Somehow, around that same time, the key was not even necessary to start it.

“It had to have been cursed,” Baylor said. “You always had to find a parking spot where you could pull out.”

Naturally, it became Santa Fe’s team car.

“You could see anybody on that team at any given time driving that automobile,” Baylor said. “Anybody who needed to go somewhere, he would let them borrow that car. He would let people drive it all over Gainesville.”

For Baylor, the old Riviera was the embodiment of Holloway’s humility. If any of Holloway’s friends or teammates needed anything, he was always there. Holloway didn’t drink (he still doesn’t), but he went to plenty of parties as a designated driver and watchful protector, especially with Boodie and his hot temper.

“He wasn’t about a whole bunch of foolishness,” Baylor said. “He would hang out with the fellas, but when things got a little too out of hand he was going to say his piece. He never condemned you if you had a problem. My issue back then was I used to drink too much. His conversation with me was always, ‘You better cut that out. You’re too good for that.’ From the day I met him, he’s been a man with integrity.

“Only thing he used to do when it came to anything against the grain was basketball. He loved to play basketball, and he was a heck of a player. That was his fun.”

Don’t play basketball was Coach Johnson’s golden rule. It was about the only one of his philosophies Holloway did not subscribe to. Everything else meshed with his hard-working, no-nonsense upbringing.

Johnson – who was the women’s head coach for USA Track and Field at the 1984 Olympics, and has coached athletes at every Olympics since 1968 – stressed the small details, a quality Holloway admired.

Showing up late was unacceptable. Johnson once chased world champion David Oliver out of practice for being late, cussing at him the entire time.

Dreadlocks or earrings were not allowed either, because Johnson constantly fought racial stereotypes and misperceptions of African-Americans. Johnson earned a degree in cultural anthropology from Tufts University, then studied law at the University of Chicago only to discover, in the 1950s, law firms would not hire him because of his skin color, and even if he waited long enough he had no interest in being a token hire.

Benevolent dictator was how Johnson referred to himself both then and today. For numerous athletes, including plenty of Holloway’s teammates, Johnson’s style never registered.

The two men forged a unique bond, recognizing plenty of themselves in one another. Behind the harsh tones and salty, sometimes even berating language, Johnson’s goal was to mold his athletes into better people. That was what truly mattered to him, and it was why Holloway bought in right from the start.

“What’s most valuable are the life lessons,” Johnson once told Orlando Magazine. “I’ve seen assholes win medals and end up being no further ahead. In the long run, they’re still bums. So are you better off winning a medal, or becoming a responsible human being?”

Holloway operates similarly to his junior college coach, minus the more ruthless aspects of Johnson’s persona.

Fiery. Authoritative. Brutally honest. Yet also lighthearted, humorous, and compassionate. It varies day to day, even hour by hour, depending on performances in training or competitions. If that sounds incredibly quirky, that’s because it is. Even more remarkable, though, is Holloway’s ability to display any one of those emotions at any given time without being off-putting. The wide array of moods and temperaments ensures he gets the most out of everyone following his lead.

Everything Holloway does traces back to a single fundamental truth: he cares. He genuinely cares about the program, about his people.

Holloway gets fiery when he knows someone can make better life choices, train harder, compete with more intensity. Nothing enrages him more than that. He jokes when he knows someone is taking things too seriously. He is empathetic when he knows someone needs a reminder of how talented they are instead of an expletive-filled rant.

The cut-and-dry honesty comes from his mother, Nelvina Holloway.

“She doesn’t dress things up,” Holloway said. “I know if I want an honest opinion … she’ll give it to me. There are a lot of people in my life I’m not sure what I’m going to get. She’s the same person. Every time. She would always tell me, ‘If you are honest and true to people, they know who you are. They don’t have to guess about what they’re dealing with.’ That’s what I appreciate about her.”

The old Riviera received its honest assessment in 1981 or 1982, Holloway believes. By that time, the muffler was gone. A mechanic told him a replacement would be worth more than his car.

Holloway laughed and said, “That was the sign we needed to let it go.”

***

Hurdling did not pan out for Holloway, his collegiate career ending after two years. The high point was a third-place finish in the 60-yard high hurdles at the 1979 NJCAA Indoor Championships.

“Mike was one of the guys that did compete beyond his fitness level,” Johnson said. “There are a very small number of people who can compete beyond their fitness level.”

Sure, he could have transferred to a four-year college and hurdled two more seasons, but his parents could not afford to help and he had no desire to sink himself into debt. Injuries slowed him down as well. Fortunately, one of them got him into coaching. As a sophomore, Holloway was sick and nursing a bad hamstring, so Johnson told him to direct the women’s 4x100 relay practice.

Life was never the same again.

“I got the sense he realized he wasn’t going to be the next Olympian,” Stone said. “From that point on, he was focused on coaching.”

After an unpaid coaching gig, a low-paying assistant coaching job at Gainesville High School, and night shifts at a local Mexican fast food restaurant kept him afloat financially, Buchholz High School made him head coach for cross country and track and field in January 1985.

Early in his tenure there, Holloway caught his big break, even though it was not apparent right away.

Holloway joined Florida’s women for the 1986 and 1987 seasons as a volunteer coach, helping the indoor 4x800 relay team break the world record. Dennis Mitchell took notice.

Mitchell made a name for himself with the Gators. The year before he exhausted his eligibility and turned professional, Mitchell finished fourth in the 100 meters at the 1988 Olympics.

By the spring of 1990, Mitchell had gone through several coaching changes. Without a pool of world-class coaches in Gainesville, Mitchell decided to go it alone, relying on his past training programs and feel to keep himself in shape.

Although Holloway’s stock boomed following Buchholz’s first state title in the fall of 1989, money remained a struggle. He had a 3-year-old daughter to provide for now, and a high school coach’s salary was just not enough. Holloway figured it was time to head back to Ohio. Mitchell, competing overseas at the time, got wind of this; he had his fiancée ask Holloway to stay in town until they could talk.

Once he returned, Mitchell went to Holloway’s apartment and asked if he would be willing to coach him.

“I just said, ‘Hey, I need some help and it would benefit both of us … let’s work together and try to get both of our goals met,’” Mitchell said. “I was attracted to Mike because he was a good guy and he was passionate. We both wanted to achieve great things, and we shared that vision together.”

Mitchell blossomed into an international sprints star at the three global championships spanning 1991-93, as he won a bronze medal in the 100 and gold with the United States 4x100 relay team at all three. When he accomplished it at the 1991 World Championships in Tokyo, the only men who beat him in the 100 – Carl Lewis and Leroy Burrell – broke the world record, with Mitchell finishing a hundredth off the original world record of 9.90 seconds. The three joined Andre Cason a week later and broke the 4x1 world record, then swapped him out for Michael Marsh and ducked under the world record again at the 1992 Olympics.

In 1990s Hollywood terms, Lewis and Burrell were Denzel Washington and Samuel L. Jackson, while Mitchell was Wesley Snipes. Lewis was already one of the all-time greats. Burrell’s rise to stardom came from a handful of marquee performances, like breaking Lewis’ world record in 1994, the same year as Jackson’s career-defining role in Pulp Fiction. Mitchell was the wild card, the action star (and, like Snipes, his reputation was damaged by personal transgressions late in his career).

They were three of the most successful men of their generation. All household names. Were it not for the other two, Mitchell could have emerged as THE icon of his era.

Coaching Mitchell at his apex jumpstarted Holloway’s career. It gave the up-and-coming high school coach credibility at the global level. And while Holloway’s work with Mitchell did not make him a rich man, it was enough to comfortably raise his daughter in Gainesville and keep his coaching dreams alive.

"God put me in Mike's life at the time Mike needed me," Mitchell said. "We both needed each other at a certain time, and we both embraced it. What we achieved back then was a foundation for what he wanted to do with his life."

All his work with Mitchell? It happened at Percy Beard Track, right outside the office he sits in today.

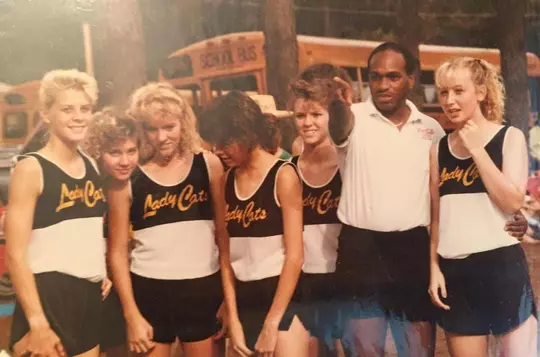

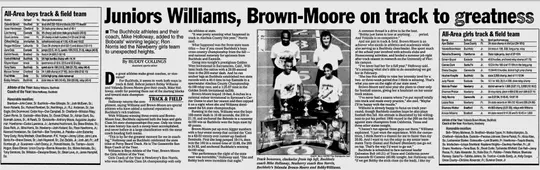

When Holloway took over at Buchholz, it had zero cross country and track and field district titles to its name. In Holloway’s 10 seasons, the Bobcats won eight state championships. The last two came in 1995, when Holloway became the first coach to sweep the men’s and women’s Class 5A state titles. He called it the greatest moment in his coaching career.

It happened right outside the window he looks through almost every day.

***

A man devoted to his faith, Holloway believes God has a plan. Viewed through that lens, every one of his life experiences prepared him to be a coach.

God’s plan for him.

Plenty of Holloway’s experiences were unique, especially when it came to jobs. He worked at McDonald’s in high school. Early in his coaching career, he was a shift manager at Krystal, a job he kept until 1987, when he was three seasons into his decade-long stint at Buchholz.

As fate would have it, Holloway’s first job was instrumental to the construction of Florida’s ongoing dynasty.

Around his 12th birthday, he began cleaning and restoring cars at Jacob’s Clean-Up, a detail shop his father owned in Columbus. It was not exactly by choice. Jacob Holloway wanted all of his children involved in the family business. Holloway, the oldest of three sons his mother and father had together, knew almost immediately it was not how he wanted to spend the rest of his life. It was good work. Honest, hard work. He just had no desire to inherit a local detail shop.

Jacob was a meticulous man with an incredible eye. He could walk past a car and point to a speck of residual wax. Same thing with engine cleanings.

“You missed a spot,” Jacob would grouse.

“It taught me to look for those things he would come behind me and look for,” Holloway said. “That taught me, when I got into coaching, to look for the little things, look for the small details.”

Bigger cars took longer to clean. Some had filthy floor mats and carpets. Cloth interiors were nightmares. Those lengthy, strenuous tasks meant getting on hands and knees and scrubbing with a brush. The more work that went into a project, though, the prouder Holloway was whenever a spotless car returned to its owner.

Pride was the foundation upon which Holloway built the Gators.

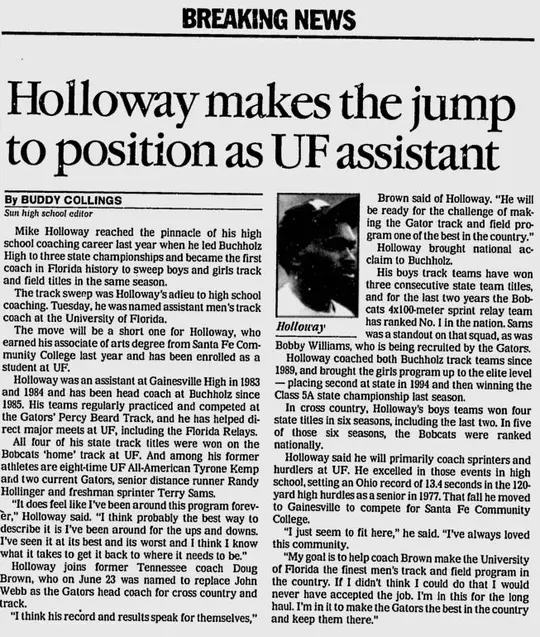

Two months after Florida poached head coach Doug Brown from Tennessee, Holloway joined the Gators as a men’s assistant coach in August of 1995, telling The Gainesville Sun, “I’m in it to make the Gators the best in the country and keep them there.”

Florida’s perception back then was that of a sleeping giant.

The Gators enjoyed a successful stretch from 1988-93, as they won an indoor Southeastern Conference title and finished in the top five nationally seven times in 12 NCAA Championships, including two runner-up finishes. Their best finish at the next four NCAA meets? A tie for 13th. Arkansas dominated collegiate track and field for much of the 1980s and all of the 1990s, winning 24 of a possible 32 national titles from 1984 through 1999. Only three programs beat the Razorbacks at NCAA Championships in the ‘90s, one of which was a Brown-coached Tennessee team in 1991, leading many to believe Brown would awaken the Gators and challenge Arkansas’ superiority.

Holloway certainly did his part. Sprinters and hurdlers combined for five individual national titles and 47 All-America honors (meaning they scored points at the national meet) in seven seasons under Brown.

The rest of the giant never woke up.

Brown only took Florida to a pair of top-four finishes at NCAA meets, the second of which came June 1, 2002, two days before athletic director Jeremy Foley announced his contract would not be renewed and tabbed Holloway as the new head coach.

To Holloway, the problems were obvious.

No long-term investment in the program’s legacy. A lack of confidence at championship meets. Too many small details overlooked.

Fortunately for the Gators, Jacob’s Clean-Up taught him everything he needed to fix it.

“I remember having a conversation as an assistant coach with a few of our athletes – Adrain Mann and Mike King,” Holloway said. “I asked them, ‘Wouldn’t it bother you guys if you left here and everything just fell apart?’ They both looked at me, didn’t even flinch, and both said no. That crushed me that day. That made me realize there was no pride at all. When I became head coach, the first thing I told everyone was we have to have pride in the Gator on our chest.

“Because of that pride we have now, we do great things,” Holloway continued. “Nobody wants to be the team that lets the program down.”

With Holloway as men’s head coach, Florida has nine team NCAA titles – all since 2010 – and 14 runner-up finishes. No other men’s program has more than five national titles or nine top-two finishes since his first season in 2003.

The Gators merged their men’s and women’s programs in 2008, effectively making Holloway the head coach of two teams.

Florida’s women have not won a national title (yet) under Holloway, but they have won eight SEC titles (five in track and field, another three in cross country) and are one of four programs to finish in the top five nationally eight times this decade. They’ve won individual national titles in distance events, as well as the jumps, sprints, throws. They’ve broken collegiate records and been finalists for The Bowerman, track and field’s version of the Heisman Trophy.

Even still, Holloway constantly fields questions about what is wrong with the women’s program. Others flat out ask him why the women aren’t any good. Neither narrative goes over very well. They agitate him to no end. Holloway recalled one recent conversation where he turned the tables on someone who posed those very questions.

“I said to this person, ‘Close your eyes, and imagine my men’s program doesn’t exist,’” Holloway said. “The women are pretty good aren’t they? The other challenge I had for them was to find a men’s program that’s as good as ours, and why they weren’t asking why the rest of the men’s programs in the country aren’t any good.

“The women are very good and they’ve had a lot of success. They just aren’t the men. But who is? It’s unfair to compare the women to that.”

Holloway takes everything personally when it comes to his men’s and women’s programs. Partly because he wants them to be a reflection of himself. Mostly because he is an intense a competitor, just like he was as a hurdler chasing an Olympic dream.

“I remember my dad telling me, ‘Whatever you decide to do in life, you be the best at it.’ That stuck with me,” Holloway said. “I’m a competitor. That’s my mindset. I don’t necessarily always think I’m the smartest guy in the room, because I know I’m not. But I believe I can be the hardest working guy in the room. I can always be that guy.”

Florida’s men rolled into the 2018 SEC Outdoor Championships as the prohibitive favorite. The women were a bit of an afterthought, with Arkansas, Georgia, and LSU pegged as the top contenders.

As the broadcast crew made their rounds and talked shop with head coaches prior to the meet, it became clear there was no women’s favorite. Arkansas and Georgia had injury issues. LSU was unsure if it had enough contributors. Holloway, sitting with his staff, eventually got wind of the chatter.

“The Gators are here,” Holloway said, keeping a straight face and casual tone. “We made the trip, right?”

Three nights later, Florida swept the team titles.

The giant is awake and stomping. Scratch that. It’s chomping.

***

In so many ways, Holloway is the same man he was back in 1977, when Gainesville became the only other home he would ever know.

“He’s the same guy,” Stone said. “He’s just a humble guy who realizes he’s been fortunate to be in places at the right time.”

Holloway’s faith is about the only thing that has changed in the years since. A devout Christian, he spreads the word of God and its impact on his life, praying every day and sharing his daily Bible verses on Facebook.

It would be logical for someone to examine all Holloway’s achieved and assume his motivation today centers around the one thing that’s missing: a women’s national title.

That would be a mistake. True to himself and the greatest influences on his life and career, Holloway’s mission has nothing to do with a checklist of accolades.

“It’s all part of God’s plan. There’s a reason we haven’t won one yet, and I have to figure that out,” Holloway said. “I just want to keep impacting peoples’ lives. If we never won a women’s championship but I greatly affected women’s lives, I could live with that. Somehow. But I don’t ever want to walk in here and feel like I don’t have a purpose, if I’m not helping somebody. As long as I feel like we’re working hard to achieve that goal, I’m okay.”

Coaching the Olympic team will not change Holloway. Only God has that power in his life. Like 42 years ago, outside his office window, where a 17-year-old high school senior unknowingly set in motion a chain of events that would influence the lives of countless men and women.

God’s plan for him.