Paul Tesori's Game Survived Q School; But His Golf Acumen Forged a 20-Plus-Year PGA TOUR Career

Paul Tesori, a member of the Gators' 1993 NCAA Championship-winning team, earned his PGA TOUR card on his first try, then injuries derailed his career and left him broke. One of the world's best players gave him a second life on TOUR, where Tesori has thrived in the two decades since.

Zach Dirlam

8/5/2020

In 27 seasons as head coach of the University of Florida men’s golf team, Buddy Alexander had plenty of what he referred to as heated conversations about tournament lineups. Truth be told, he loved those discussions. They revealed exactly how competitive his young golfers were.

Plenty of Alexander’s Gators enjoyed successful PGA TOUR careers. Chris DiMarco once ranked No. 6 in the world and finished second in three of golf’s four major championships. Billy Horschel won the 2014 FedEx Cup and is a five-time winner on TOUR. Camilo Villegas ranked as high as No. 7 in the world and finished second in the 2008 FedEx Cup Playoffs. Brian Gay joined the TOUR in 1999 and still makes his living on the professional circuit.

One of most intense player-coach meetings Alexander ever had, though? It was not with a future TOUR star. It was with Paul Tesori.

While Tesori’s brief stint as a PGA TOUR golfer ended without a single made cut, he is in his 21st year as a caddie, and 10th season on the bag for Webb Simpson. Ranked No. 4 in the Official World Golf Ranking and second in the latest FedEx Cup Standings, Simpson enters this week’s PGA Championship as one of the hottest players on TOUR. The symphonic relationship between Tesori and Simpson is often attributed to the latter’s ascent into professional golf’s upper echelon.

Count Tesori’s former coach among those believers.

“I think he’s one of the best caddies in the world today,” Alexander said. “He’s got the advantage of being a good player, he’s likable, he’s spiritual, he’s competitive as hell, and just an overall great guy to be with. And he knows the game.

“How many guys caddying on TOUR today actually had their PGA TOUR card? Not many.”

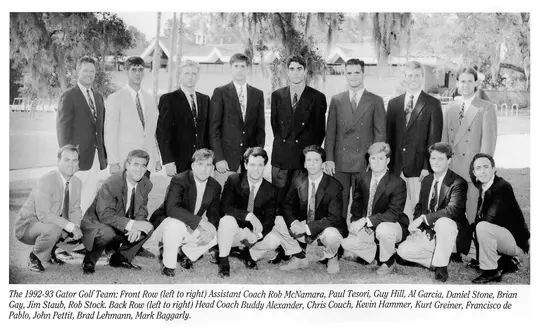

Back in the summer of 1992, Tesori joined the Gators as a coveted junior college transfer. Although he grew up in a Florida State family in St. Augustine, Fla., Tesori visited Florida with an open mind. Competition was the foundation of Alexander’s program, and it ultimately secured Tesori’s commitment. Tesori broke the news to his father, a Florida State graduate, and headed to Gainesville with championships and the life of a TOUR pro on his mind.

Balance, however, was a struggle for Tesori once classes started. He quickly discovered the academic expectations at UF were vastly different than the junior college ranks, where he breezed through coursework with minimal effort and focused almost entirely on golf.

A tournament early in the season put him two days behind in calculus. Those math equations might as well have been hieroglyphs upon his return.

About the only silver lining for Tesori was the fact his teammates fell behind as well. The primary reason for the team’s fall-semester issues? An addiction to Nintendo’s Tecmo Football. Homework and exams were hardly relevant when someone had to stop Randall Cunningham and the Philadelphia Eagles (arguably the game’s most dominant team with Bo Jackson and the Los Angeles Raiders being off limits). Tesori and the Gators even formed a league among themselves, routinely playing games well into the night.

“The rule was, if you fell asleep, your game was simulated,” Tesori laughed. “If you lost, you weren’t going to have home field advantage, which used to matter back then. If you won the season, you got to pick your team the next year. But if you fell asleep, it was tough luck.”

Alexander eventually instituted mandatory weekly study hall sessions at the golf course – which became known as Buddy Hall – to, in his words, “make sure their time was well spent.”

Imbalanced academically and athletically, Tesori made the five-man travel lineup twice in his first season. Hence the heated conversation with Alexander.

“There was some immaturity coming in that I didn’t realize at the time,” Tesori said. “As a 21-year-old, you pretty much think you’re the smartest person around. Coach Alexander had to chisel some of that away.”

Although Tesori traveled to the Southeastern Conference and NCAA Championships in the spring of 1993, he went as an alternate. Reduced to a non-playing role as a motivator and confidence booster for his teammates, Florida’s victories at those tournaments were bittersweet for Tesori. He celebrated the Gators’ titles, but it was difficult to stomach the fact Alexander deemed him unworthy of a spot in those lineups, along with the fact it strained their relationship.

“Everybody on the team loved Paul,” Alexander said. “Everybody still loves Paul to this day. The second year, when he started to play and go to tournaments, we became much closer. I understood Paul a little bit better.

“Paul was just a determined, dogged competitor that got a lot from his game.”

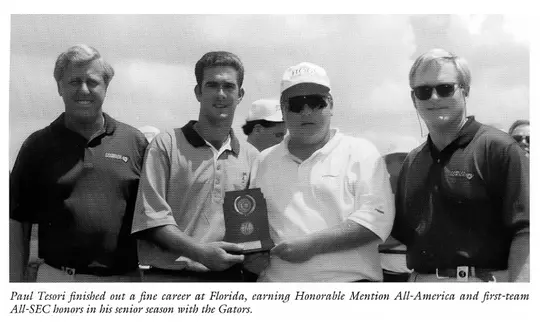

Tesori adjusted his habits on the course and in the classroom ahead of his senior season. Alexander played him in the No. 1 spot all of 1993-94, and Tesori finished second on the team in scoring average.

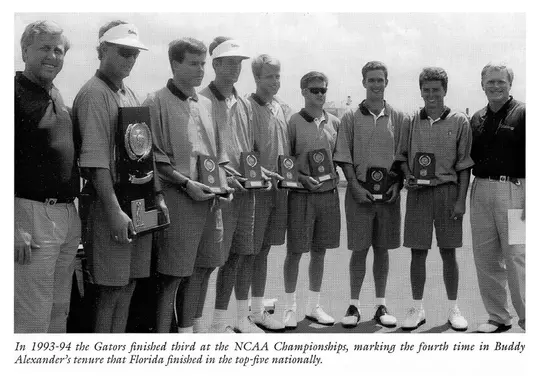

The Gators cruised to a second consecutive SEC title, and took third at the NCAA Championships. Tesori took 13th individually and scored All-America honors with a 3-under par week at nationals. Florida finished seven shots behind Stanford in its effort to repeat as NCAA champions.

“(Stanford’s) William Yanagisawa shot 64 the last day against me,” Tesori said. “I shot 1-under; he shot 8-under. We lost by seven. It was something I carried with me. I was never going to be able to match that 8-under par round.”

As it turned out, Tesori never had to.

***

In a 1996 story which detailed the PGA TOUR Qualifying School – better known as Q School – Vartan Kupelian of the Detroit Free Press wrote, “Q School will give some men religion, lead others to drink, and, sadly, become the final resting place for too many hopes.”

Surviving every cut at Q School was, in many ways, harder than keeping what was originally its ultimate reward: a PGA TOUR card. (The 2012 Q School was the last to award such cards, after which the TOUR overhauled its qualifying system. Today’s version is far more restrictive in terms of entry requirements, and no longer provides a direct path to the TOUR.)

One bad hole. One errant shot. One miscalculation. Those are often the margins between great, good, and bad rounds of golf at the sport’s highest levels.

A bad round on TOUR likely means a missed cut, a week of expenses and no prize money to pay them with. But there is a tournament seemingly every week on the professional circuit, and even the entry-level cardholders have access to the vast majority of them. There will be other money-making opportunities. It just boils down to a tough week at the office.

A bad round at Q School? A missed cut there instantly ended a lifetime’s worth of work. Better luck next year, fella.

Tesori stayed in Gainesville for two years after his senior season, earned his degree, and sharpened his game for a run at Q School. For cost-efficiency purposes, Tesori and Chris Couch, a teammate and one of his closest friends in his two seasons with the Gators, entered together in 1996 and shared a hotel room throughout each stage.

Pre-qualifying tournaments and the first stage of Q School were 72 holes apiece, just like a four-day PGA TOUR event. Out of the 1,000-plus entrants, only 188 souls advanced to the second stage.

Those survivors regathered themselves for about a month and headed to California for the last stage – six more pressure-packed rounds, with yet another cut after 72 holes. Only the top 40 and ties earned PGA TOUR cards. The next 70 received Nike Tour status (known as the Korn Ferry Tour today), effectively putting them in golf’s version of Triple-A baseball.

“It’s the biggest grind in golf,” Couch said.

Rounds of 77, 71, 72, 69, and 71 (even par for the week) left Tesori tied for 37th place with 13 other players. Right on the cut line for TOUR cards.

The sixth round of the final stage was cancelled due to unplayable weather conditions.

“I didn’t really put a whole lot of pressure on getting my card … and that’s probably one of the reasons I got my card,” Tesori said. “I wanted my Nike (Tour) card. I knew I needed to get better. I needed to learn how to travel, how to play in front of fans. I was out of my element.”

In order for a player to keep his TOUR card in Tesori’s era, they needed to finish in the top 125 of the season’s money list, or win a tournament. Failure to achieve either feat meant a return to Q School.

Tesori played 12 PGA TOUR tournaments in 1997, missing eight cuts, withdrawing from three others, and disqualifying himself from the last one. Rotator cuff and labrum tears took a significant toll on his game and forced him into a year of rehabilitation.

Debilitated physically and completely broke financially, Tesori moved back into his parents’ home. Any confidence he had left dissipated shortly thereafter.

As Tesori worked himself back into form and received major medical extension status for the 1999 PGA TOUR season, giving him an opportunity to regain his card, he struck up a friendship with Vijay Singh, best known at that time for his victory at the 1998 PGA Championship. The two developed a relationship at TPC Sawgrass in Ponte Vedra, Fla., where Singh lived throughout his years on the TOUR. Whenever Singh wasn’t on the road for a tournament, he logged eight-hour sessions at the driving range. Every day. Without fail.

Tesori, on the other hand, loathed practice; he just wanted to play 36 holes a day. Chipping, putting, or approach contests against his buddies? He loved those. Hitting range balls for hours on end? He couldn’t even stand the thought.

Singh gave Tesori some advice: practice more, play less. The two even had a friendly wager. If Tesori spent 10 hours at the driving range for five consecutive days, Singh owed him $100 for each day.

No rounds. No contests. Just basket after basket of range balls, chipping exercises, and putting drills.

“A lot of money back then for a guy who was trying to pay bills week to week,” Tesori said. “Vijay has kind of earned a little bit of the reputation he’s gotten, just for maybe being a little too cold at times toward media and fans, but Vijay’s got a great heart. He did that because he cared about me, cared about a young player he knew was going through a tough time. And he was trying to teach me a different kind of work ethic than I had previously known.”

While Tesori learned an important lesson, his second PGA TOUR stint was no different than the first.

Seven missed cuts, one withdrawal, one disqualification.

Tesori survived Q School. The TOUR ate him alive.

***

Competitive golf is a lonely endeavor, and life on the professional circuit is a lonely existence. It can also get expensive for the game’s true grinders, the players hardly anyone ever sees on television.

Most TOUR pros spend anywhere from 25-30 weeks a year on the road. Same goes for players working their way through the less-lucrative mini tours or international circuits. (For example, only 59 players made at least $100,000 on the Korn Ferry Tour last year, and its 2019 money leader played 20 events and made $565,338, a total exceeded by 158 PGA TOUR players last season.) Players are responsible for their travel and hotel costs. Those expenses add up in a hurry, especially when local hotels increase their rates the week of TOUR events. And that’s without even considering their family’s financial obligations back home.

Whenever a player misses a cut and either heads to the next tournament, or goes home having essentially lost money, failure is entirely theirs to bear. And when part of a golfer’s game is out of sync, or things start going sideways during a round, there is no teammate to pass the ball to, no running game to transition to until the passing game opens up.

Golfers only have themselves, the next shot, and all the voices rattling around in their heads.

Tough times in golf wage wars within the mind. Sometimes it ends after a single round. Other times it spans several tournaments. Golf’s grinders either win those inner battles, or succumb to the burden of them, drive themselves into the abyss and wind up as nothing more than a local legend telling stories from their glory days in the show. Even the best players in the world fall victim to those internal struggles for extended stretches.

The best caddies in the world provide a sense of companionship for their golfers.

A caddie’s role changes constantly, because every golfer has their own needs and expectations. Some just want a confidant, a friend who will talk about anything except golf between each of their shots. Others want someone to simply carry the bag, calculate the yardages, occasionally read a putt, and just be a rock to lean on when things get difficult. A select few use caddies as a second swing coach. Several of them value the perspective a former professional player brings to the table when it comes to diagnosing and talking through every situation on the course.

Cheech Marin’s performance as Romeo Posar in Tin Cup, an endlessly-rewatchable classic, showcases a caddie dealing with plenty of fictional extremes. The vast majority of the movie is both hilarious and outrageous, but its most beautiful moments center around Marin’s remarkable depiction of a caddie managing the job’s personal intricacies.

“I try to tell everyone one of the biggest things of caddying is being a psychologist. It’s understanding the guy you’re working for … it’s being focused on the (practice) range, and also understanding what your guy might be going through. Just understanding what nerves are going to do to the body, what anxiety is going to do to the body, what adrenaline is going to do, and being able to make those kinds of decisions in the moment.”Paul Tesori

Tesori never set out to be a caddie. In fact, without Singh’s interest in him as a struggling TOUR pro, it is unlikely Tesori ever winds up with anyone’s golf bag over his shoulder.

Shortly after Tesori lost his TOUR card, he accepted a golf pro position with a $22,000 salary at White Oak Plantation’s Legacy Course in Yulee, Fla., a small commuter town near Jacksonville.

Ahead of the 2000 PGA Championship in Louisville, Ky., Singh, the No. 9-ranked ranked player in the world who won his second career major at the Masters Tournament earlier that season, reached out to Tesori. Singh wanted some swing advice and, in exchange, secured a teaching credential for Tesori.

While Tesori solicited advice throughout the week, the trip was essentially an interview for a different job. Singh was in the market for a new caddie.

All Thursday and Friday, Tesori followed Singh’s group around Valhalla Golf Club. The other two men in the threesome? Tiger Woods and Jack Nicklaus.

Woods had already won the U.S. Open and Open Championship in record-setting fashion that season. Nicklaus, golf’s all-time record holder with 18 major championship victories, was 60 years old and entered in his final PGA Championship.

“I’ve never seen that many people following a group in my life. Even Vijay was out of his element,” Tesori said. “Vijay was the villain in that group. Everybody was rooting for Jack Nicklaus and Tiger Woods.”

As the trio walked up the 18th fairway Friday, Nicklaus stood two shots off the cut line with a wedge in his hand. Nicklaus nearly holed out, missing an eagle by mere inches before tapping in for birdie and finishing at 4-over par.

Tesori hung around for the weekend and watched as Woods and Bob May set the PGA Championship scoring record with matching 72-hole scores of 18-under par. Woods defeated May by a shot in a three-hole playoff, winning the third leg of what became known as the “Tiger Slam” after his victory at the 2001 Masters.

Singh posted the same score as Nicklaus and missed the cut. Tesori took over as Singh’s caddie the following week.

Tesori’s first decade as a caddie was full of highs and lows. The peaks with Singh were a pair of victories in 2002, and an incredible Tiger story he will be telling for the rest of his life.

.@PaulTesori, PGA Tour Caddie, shares a story behind wearing a "Tiger Who?" hat.

— Dan Patrick Show (@dpshow) June 26, 2020

For Paul's full appearance: https://t.co/0NPHTqNGNn pic.twitter.com/HFLexV2EsD

Tesori and Singh mutually parted ways in 2003. The combination of time spent away from home and his family – both at tournaments and Singh’s lengthy practice sessions – wore on Tesori, who once told Golfweek he had a combined 24 days off in his initial stint with Singh.

“There wasn’t a whole lot of time for the rest of life,” Tesori said in the story. “I lost a marriage over it. I wasn’t willing to change my job because I knew obviously it was the chance of a lifetime financially.”

Six weeks after the split with Singh, Tesori had already accepted a job as a bank teller in Florida when two-time TOUR winner Jerry Kelly called. A normal life could wait. Tesori still wanted a bag on his shoulder.

Kelly and Tesori were together two years, with the high point being a trip to the 2003 Presidents Cup in South Africa. More importantly, Tesori noted the 2003 season “really cemented (his) reputation” on TOUR.

A reunion with Singh during his ascent to the world No. 1 ranking, followed by part-time work with Couch held Tesori over until 25-year-old Sean O’Hair called late in the 2007 season. O’Hair made a splash with his victory at the 2005 John Deere Classic, and already had a trio of top-15 finishes in major championships to his name.

“We decided (a mutual split) was the best thing for him,” said Couch, who only made 10 cuts in his 30 starts in 2007. “I’d always had decent caddies, but Paul was on a different level. Unfortunately, I didn’t play up to par with him. A lot of these caddies depend on their players. If you’re not making money, they’re definitely not making money. He was used to making a certain amount a year, and he wasn’t even coming close to that with me.”

O’Hair won twice and logged 15 top-10 finishes – including a tie for 10th at the 2009 Masters, and a tie for seventh at the 2010 Open Championship – in three years with Tesori on the bag. At the end of a rocky 2010 season, though, O’Hair fired Tesori.

Combined with the fact the 2008 financial crisis washed away his career earnings, Tesori was jobless and broke all over again. Somehow, he found himself completely at peace for the first time in his life.

Another positive: two established TOUR players offered Tesori their bags. Both were in the top 15 of the Official World Golf Ranking during the 2010 season.

Neither felt like fits for Tesori, who wanted a long-term relationship with whoever he worked for next. Another short stint was better than a season without a job, though. Tesori made his choice and was an hour away from a confirmation call.

Then Simpson got ahold of Tesori.

“Five minutes into the conversation, I was like, this is what I’ve been waiting for,” Tesori said.

When Tesori called Couch and broke the news, his longtime friend asked with a deadpan tone, “Who’s Webb Simpson?”

***

Purely from a golf perspective, Simpson and Tesori were an unlikely pairing when they first spoke on the phone.

Simpson was outside the top 200 of the Official World Golf Ranking and barely retained his TOUR card for the upcoming season.

Spiritually, the two were a perfect match, with both men being devout Christians. They bonded over scriptures and Bible verses right from the onset, and they developed a friendship which blossomed into one of the most renowned player-caddie relationships on TOUR.

In their first year together, Simpson won two tournaments, rose to No. 10 in the world rankings, took second in the 2011 FedEx Cup Playoffs, and finished second on the TOUR’s money list with more than $6.3 million in earnings.

“Paul is an equal part of the team,” Simpson told The Florida Times-Union that season. “If he comes to the golf course and he’s mentally not ready to play, then it affects me. A lot of guys don’t rely on their caddie as much as I do, which is fine. But I rely on him pretty heavily.”

Simpson solidified himself as one of the game’s rising stars at the 2012 U.S. Open in San Francisco.

It was Simpson’s fifth major championship appearance, and it actually almost ended well before the start of Thursday’s opening round.

“He wasn’t himself Monday, Tuesday,” Tesori said. “He kind of broke down on the putting green and just told me, ‘My son just took his first steps, and I missed them. I don’t want to be here. I don’t want to miss those things.’ His wife ended up flying out … she was, I think, almost eight months pregnant and walked every hole. We’d missed the two previous cuts, but we worked on some things Wednesday that got a little better Thursday, a little better Friday.”

The Olympic Club provided a classic U.S Open test, one where the winning score was expected to be even or over par. The 26-year-old Simpson fired consecutive rounds of 68 (2-under par) Saturday and Sunday – which made him the only player in the field to break par both weekend rounds, and one of only seven to accomplish the feat Sunday afternoon.

Simpson carded four birdies and nine pars across Olympic Club’s final 13 holes Sunday en route to a 72-hole score of 1-over par.

“The amazing thing for me was to watch … he seemed so calm,” Tesori said of his partner’s phenomenal closing stretch. “I knew he wasn’t calm on the inside, but we had an incredible up and down on 18, where it was the worst lie you could ever imagine up by the green. It was (in) an older sprinkler head … an old sod patch that had browned out, and it was up against that four-inch rough. We were trying to chip that ball to 10 feet. It came out miraculously well to three-and-a-half feet; he played the putt just outside the left edge and made it.”

Tesori and Simpson watched from the clubhouse as fan favorite Jim Furyk faded late, and 2010 U.S. Open champion Graeme McDowell’s potential playoff-forcing birdie putt at the 18th hole ran well past the cup.

The first congratulatory call Tesori received?

It came from none other than Vijay Singh.

Winning the U.S. Open remains the biggest moment of Simpson’s career, but his dominance of the 2018 PLAYERS Championship at TPC Sawgrass is Tesori’s favorite memory of their journey thus far.

For one, the runaway victory at Tesori’s old stomping rounds propelled Simpson to his first top-10 finish on the TOUR’s money list since 2011. Simpson tied the course record that week with a 9-under par 63 Friday, despite a mysterious swirling wind at the famed par-3 17th – which led to a club change, a shot into the water hazard, and a double bogey.

It also pulled Simpson out of the slight funk he entered after the U.S Open win. The rut was amplified by the TOUR’s ban of anchored putting, a style which made Simpson one of the game’s elite putters. Simpson’s adjustment took about three years, and he actually improved as a putter once the awkwardness of his new technique wore off.

“Paul's been just a great friend through all of this,” Simpson said after his four-year winless stretch ended at the PLAYERS. “I never thought once that he would quit and go work for somebody else, but … I expected him to be frustrated at times, and he never was. He stayed positive. To go through that, you need someone more than a caddie. You need a friend. He definitely was that for me.”

Simpson was 10th on last year’s money list and, with two victories already this season, is well on his way to another impressive haul. Tesori earns seven percent of their winnings.

Today, the two men are closer than ever in all aspects of their lives.

Given the TOUR’s approach to player and personnel safety amid the COVID-19 pandemic, Simpson and Tesori are rooming together on the road. This is a return to old times for them. Few players of Simpson’s stature room with their caddie as frequently as he and Tesori (about eight weeks a year prior to the pandemic). Most remain separate in that regard. It serves as another example of the unique relationship Simpson and Tesori have with one another.

“We’re spending a lot of time in the hotel room, which is right up my alley,” Tesori said. “He doesn’t like to be caught up in a hotel room; he’d rather be out … (prior to the pandemic) he’d go work out, have Starbucks and relax. I’d go back to the room, put my sore feet up, and we’d get together for dinner.

"I’m teaching him what to do to stay busy. We’ve got rollers. We’ve got bands to stay in good shape. We’ve got movies to watch. I’m having a good time.”

On the course, Tesori equates their decision-making process to that of a catcher calling a baseball game for his pitcher. Simpson likes to talk everything through. Tesori knows every shot in Simpson’s bag, and processes all the information he gathers – yardage to the chosen target, pin location, wind direction and strength – as he calculates which one best aligns with their strategy. The two read putts together as well.

“The longer you’ve been together, the easier those things are,” Tesori said. “Webb hates it when I call him boss, but I do think it needs to be that 60-40 mentality, because he has to hit the shot. My job is to give him the information that I’m feeling, that I’m seeing, that I’m writing, but he’s got in his hands the way he feels in that moment. He knows what he’s feeling. He has to take ownership.”

This week’s PGA Championship will be the first of 2020’s three majors (the pandemic led to the Open Championship’s cancellation, while the U.S. Open will now be in mid-September, followed by the Masters Tournament in November). It was also supposed to mark the duo’s triumphant return to San Francisco.

TPC Harding Park, a municipal course along the northern shore of Lake Merced, is hosting one of golf’s majors for the first time since its establishment in 1925. The grounds did, however, infamously serve as a parking lot for the 1998 U.S. Open at Olympic Club, which sits across the lake and along the Pacific Ocean.

Instead of toting Simpson’s 50-pound staff bag and navigating a challenging layout, Tesori will be watching from home.

Back and hip pain forced Tesori off the bag last weekend in Memphis.

So many nice responses. Thank you for the thoughts and prayers! Also, I missed tournaments with the birth of my son and shoulder surgery but I have never missed a tournament day when I was supposed to work! Just had to get that moral honesty out! Haaa!!! https://t.co/7yMy9emtMf

— Paul Tesori (@PaulTesori) August 2, 2020

Tesori will be a nervous golf fan all week as his friend takes on disconcerting dogleg angles, firm greens guarded by treacherous bunkers, and narrow, curving fairways bordered by thick rough, and towering cypress and eucalyptus trees. Such a setup typically favors a player like Simpson, a tremendous ball striker who performs best on courses which reward precision and neutralize distance off the tee.

This week’s layout is exactly what Tesori loved when he teed it up for the Gators. Iron play and a fairway-finding Wilson Firestick 3-wood were Tesori’s greatest assets at Florida.

“There was a time when I was at Florida when I wondered if it was the right decision,” Tesori said. “When I look back, it was the smartest decision I ever could have made. So much of what I’ve been able to accomplish was because of the University of Florida, because of the golf team, because of Coach Alexander, and the guys around us.”

These days, Tesori relies on an artistic short game rather than his irons and tee balls. Not exactly a recipe for success in a major championship. Fortunately for Tesori, he doesn't have to hit the shots anymore. Simpson takes care of that for both of them.

And hopefully it isn’t long before they are walking the course as a team again.

To learn more about Paul Tesori and his family, follow this link for information about the Tesori Family Foundation.