How Tough is a U.S. Open at Winged Foot? Plenty of Gators Know All Too Well

“You're going to get beat up. It's just whether you're going to get knocked out." --Andy Bean

Zach Dirlam

9/16/2020

MAMARONECK, N.Y. – To steal a quote from the man himself, Gary Koch knows this year’s U.S. Open venue better than most.

Winged Foot Golf Club’s West Course is hosting its sixth U.S. Open, with Koch making his fourth appearance. Koch, a three-time All-American and two-time Southeastern Conference Championship medalist in his four years with the Gators, played Winged Foot in the 1974 and 1984 U.S. Opens. By the time the tournament returned there in 2006, Koch was an on-course reporter for NBC’s television broadcast. Between his firsthand knowledge of the course and conversations with Dan Hicks, a club member and lead anchor for NBC’s golf coverage the last 20 years, Koch knows exactly what this week has in store for the best golfers in the world.

“Guys will struggle to break par,” Koch said of the 144-man field, which includes two Gators – sophomore Ricky Castillo and 2014 FedEx Cup champion Billy Horschel.

Designed by famed course architect A.W. Tillinghast and brought to life in the 1920s, Winged Foot has a reputation for bludgeoning its challengers. Even by U.S. Open standards.

Champions often hover around even par, but only one other course in the tournament’s 125-year history – Oakland Hills Country Club, also a Tillinghast creation (there was a reason they nicknamed him “Tilly the Terror”) – lists more than three over-par winners.

Four of the previous five U.S. Opens at Winged Foot ended with the entire field at least two strokes over par. The outlier was 1984, when Greg Norman and Fuzzy Zoeller both finished 4-under par. Aside from Norman and Zoeller, no one else reached the iconic, Tudor-style clubhouse of this fabled beast of a golf course with a 72-hole score better than 1-over par.

Winged Foot’s sharp teeth come in the form of severely-sloped green complexes. These things are tougher to navigate than political conversations at a family holiday party.

Easy two-putts and routine par saves are practically nonexistent when players find themselves on the wrong side of even the most generous pin placements.

Further complicating matters, deep bunkers protect these already devilish greens. Blasting out of the sand is not an issue. The lack of flat areas on the greens, however, makes those traps incredibly penalizing.

“Invariably, you had to land the ball on the downslope,” Koch said of his experience with the greenside bunkers. “It was almost impossible to get the ball anywhere near the hole.”

Coupled with the United States Golf Association, the tournament’s governing body, ensuring firm and fast course conditions, wayward approaches bring all sorts of numbers into play. Especially when players must contend with the most defining characteristic of U.S. Open setups: long, gnarly rough. Lies in this stuff are usually worse than a direct-to-streaming movie starring Nicolas Cage.

With this rough, you don't want a shot from here on No. 18 at Winged Foot. ?? pic.twitter.com/6bnzZYaPEj

— Golf Digest (@GolfDigest) September 14, 2020

Those factors put a premium on hitting fairways. Finding the short grass is a tall order at Winged Foot, though. Like the greens, flat spots are few and far between. Missing the proper landing area by a yard or two can easily send a picturesque tee ball rolling into the rough.

“Winged Foot is a difficult course. That’s all there is to it,” Koch said. “It’s a heck of a test. For those of us old guys, that’s the identity of the U.S. Open. The U.S. Open was always the toughest test.”

As Koch alludes to, golf’s four major championships have signature qualities which shape their individual identities.

The Masters Tournament, renowned for its blooming azaleas and immaculate presentation, comes down to the Sunday chess match that is the back nine of Augusta National Golf Club. The Open Championship (also known as the British Open) is the oldest major, tracing its roots to 1860, and typically boils down to dodging crummy weather and withstanding the prevailing winds on the historic links courses. The PGA Championship is a celebration of club professionals across the country, most often presenting a moderate challenge and producing some of the more surprising major champions (think Rich Beem, Shaun Micheel, Y.E. Yang, and a ninth alternate named John Daly).

The U.S. Open is golf’s equivalent of a heavyweight prize fight.

Every escape from the deep rough exacts a physical toll, regardless of a player’s strength. Narrow fairways, firm greens, and well-guarded pin placements test the acumen and patience of even the game’s best tacticians. Repeatedly scrambling around the greens eventually wears on everyone’s psyche. Aggressive play might generate an extra birdie or two, but it also opens the door to tournament-ending double and triple bogeys.

Translation: par is a hell of a number in this tussle.

Just ask Andy Bean, who played with Koch at Florida, garnered three All-America honors, and racked up 11 PGA TOUR victories. He stepped into the ring 16 times.

“You’re struggling all week, and that’s not a good feeling,” Bean said. “It drains you. You get a little bit too far behind and you want to catch up, instead of accepting shooting two over, three over on one nine and making it up the next 36 holes. Your nature is to try to get it back. If you start trying to press and get too much out of your round, it’s going to jump up and bite you.

“You’re going to get beat up. It’s just whether or not you’re going to get knocked out.”

Bean and Koch each got their first dose of the U.S. Open as collegians.

The USGA has a longstanding tradition of allowing amateurs, provided they have a handicap of two or less, to tee it up with golf’s top professionals. Eligible amateurs compete against non-exempt pros in local and sectional qualifiers. In the 1970s and 80s, upwards of 5,000 entrants competed across the country for roughly 100 spots not filled by exemptions.

As a junior at Florida in 1973, Koch qualified with a win at a sectional in Pittsburgh, Pa. Bean, a sophomore, won a sectional in Atlanta and rounded out the 150-man field bound for Oakmont Country Club, another notoriously difficult U.S. Open venue.

Bean missed the 36-hole cut by three strokes at Oakmont. Koch, one of two amateurs who played the weekend, finished 18-over par and took 57th place. Johnny Miller started Sunday’s final round six shots off the lead and shot an 8-under par 63, the lowest round in U.S. Open history, winning the tournament in stunning fashion.

Six days later, Koch (second) and Bean (tied fifth) led the Gators to a team national title at the NCAA Championship in Stillwater, Okla.

The following year, Bean and Koch emerged from local and sectional qualifiers for the third U.S. Open at Winged Foot, which previously hosted the tournament in 1929 and 1959.

The two Gators met at the West Course for a Monday practice round. Bert Yancey, a seven-time winner on the PGA TOUR they recognized from his handful of top-five finishes at major championships, joined Bean and Koch on the first tee.

For two shots, all was well. Then came Yancey’s 30-foot birdie putt down the hill of the severely-sloped first green.

“He hits this putt, and it rolls, and it rolls, and it rolls, and it rolls right off the front of the green. It went at least 60 feet,” Koch said. “He walks by, gets his ball, and starts walking back down the first fairway, cursing the USGA the entire time. We never saw him again. He just walked in. Bert was a different cat, but it was very eye-opening for Andy and I to see this happen right in front of us.”

Another Gators alum, Wally Armstrong, had an equally unnerving experience in his practice round with Gary Player.

Armstrong played three seasons at Florida and was an All-American in 1966, his junior year. Between the time he earned a master’s degree, completed a stint in the U.S. Army, and made multiple trips to the pressure-packed PGA TOUR Qualifying School, Armstrong caddied for fellow Florida alum Dave Ragan, a three-time winner on TOUR. Armstrong also caddied for Player three times, with the two forming a lasting friendship.

By the time they arrived at Winged Foot in 1974, Player was a seven-time major champion (he eventually won nine) and widely considered one of the greatest golfers of all time. Player was also two months removed from a win at the 1974 Masters, while Armstrong was midway through in his TOUR season.

“The rough was so high,” Armstrong said. “If you hit it in the rough, you just took a sand wedge out of your bag. You knew you just had to hack it back in the fairway. I had never experienced anything like this.”

Steve Melnyk, a college teammate of Armstrong’s, was another one of the seven Gators in the field. In a Golf Digest oral history of the tournament, Melnyk said there were six balls in his bag when he began a practice round on No. 10 tee. He ran out before his eighth hole.

“I hit two tee shots on 17 into the right rough and couldn’t find either one of them, and I was out of balls,” Melnyk said. “I hadn’t hit one out of play, but I was done.”

Koch went as far as to say Winged Foot’s setup in 1974 was as “close to impossible to play” as he ever experienced.

There were areas on the course with 8- and 10-inch rough. Fir trees along the fairways were not limbed up, which literally brought players down to their knees for punchouts. The greens were so fast, Jack Nicklaus famously (or infamously, depending on the viewpoint) rolled a 30-foot putt off the first green and had a 35-footer back up the hill for par. They were like concrete. Literally. Prior to Friday’s second round, a Winged Foot grounds crew member discovered automobile tire tracks on the first green. Once it was cut that morning, there was no evidence anything out of the ordinary ever happened.

The week ended with just eight under-par rounds, one of which belonged to Frank Bead, a Florida alum and the 1969 PGA TOUR money leader.

The winning score? Seven-over par, shot by Hale Irwin.

Koch and Armstrong missed the cut at 17- and 19-over par, respectively. Bean made the cut and shot weekend rounds of 83 and 81 en route to a tie for 64th place at 34-over par. Melnyk’s 22-over par tied him for 35th, while Beard tied for 12th at 15-over par, one stroke behind Nicklaus, and two behind Player.

Dick Schaap later wrote a book with a minute-by-minute account of the week. Massacre at Winged Foot became the unofficial name of the 1974 U.S. Open following its publication.

Some believed the setup was a result of Miller’s record-breaking 63 the year before. Many wondered aloud if the USGA intentionally embarrassed the field. Although USGA officials admitted the course was too difficult, the man responsible for the setup, Frank “Sandy” Tatum, never relented.

“We’re not trying to humiliate the best players in the world,” said Tatum, who served on the USGA Executive Committee from 1972-80. “We’re simply tying to identify who they are.”

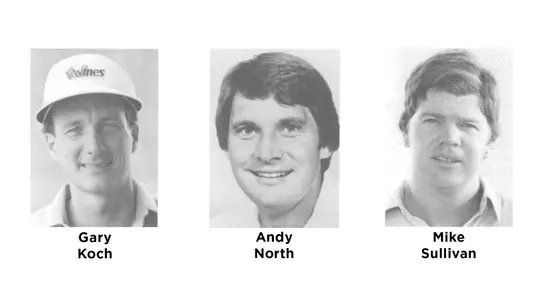

Andy North was one of the men the USGA identified before the U.S. Open returned to Winged Foot in 1984.

Another three-time All-American for the Gators, North turned professional following his senior season in 1972 and picked up his first PGA TOUR win at the 1977 American Express Westchester Classic. The following year, at Colorado’s Cherry Hills Country Club, North jarred a 12-foot birdie putt on No. 13 and took a five-shot lead into the closing five holes of the 1978 U.S. Open. Although he stumbled toward the clubhouse, North clinched the major championship with a sublime bunker save for bogey on the 18th.

“I really did enjoy playing the Open,” North said. “It fit my mentality well. You just had to figure out a way to make pars, hang in there, and be tough.”

North’s victory at Cherry Hills was his exemption for the 1984 U.S. Open.

Bean and Koch made the field as a result of their top-30 finishes on the 1983 PGA TOUR official money list, as well as their top-10 standing among the 1984 money leaders. Koch picked up two of his six career PGA TOUR wins in the leadup to Winged Foot. Bean, one of the longest hitters on TOUR, won the Greater Greensboro Open a little more than two months before June’s U.S. Open.

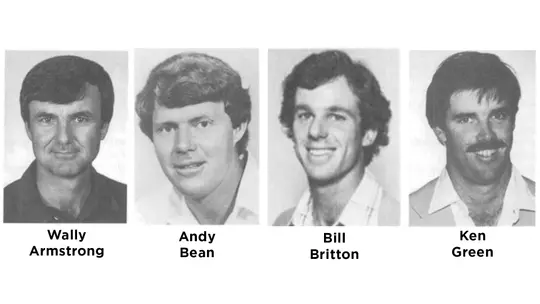

Of the other 13 Gators with TOUR cards, one of the largest contingents from any collegiate program at the time, only four earned U.S. Open berths via local and sectional qualifying: Bill Britton, Ken Green, Mike Sullivan, and Armstrong, then in his final season on TOUR.

John DeForest would not earn his TOUR card for the first time until season’s end, but the former Gators walk-on who said he never made the travel roster in college gave Florida an eighth representative. The only NCAA school with more alums in the field was Houston, which had nine qualifiers.

Players were nervous about another USGA setup at Winged Foot. Given what happened the last time, who could blame them?

The 156-man field was satisfied when they found shorter cuts of primary rough, more receptive greens, and slightly wider fairways. Traffic, however, was a significant issue, one which drew the ire of numerous players and the attention of national columnists.

“It was gridlocked,” Sullivan chuckled. “You’d move 10 feet in 10 minutes. I saw a golfer just carrying a golf bag, walking down the road, and they were making better time than anybody else.”

The course once again battered its competition.

A mere 23 players carded an under-par round. Only five broke par twice. DeForest played alongside one of them, a mini-tour regular named David Canipe.

After consecutive 1-under par 69s Thursday and Friday, Canipe charmed the media with tales of hustling on the mini-tours and surviving a 14-hole playoff in his sectional qualifier. Canipe entered Saturday’s third round two strokes behind Irwin, who led with a pair of 2-under par 68s. Weekend scores of 81 and 83 dropped Canipe into a tie for last place among the 63 men who made the cut.

Half the Gators survived the 36-hole cut. Britton, who grew up an hour away from Winged Foot, was one of the four.

“For me, having the U.S. Open there, it was the Super Bowl,” said Britton, who tied for 60th and enjoyed a 15-year PGA TOUR career highlighted by a win at the 1989 Centel Classic. “The whole experience was just a thrill.”

Koch was steady throughout the week and tied for 34th, while Bean closed with a 1-over par 71 and tied for 11th as the rest of the field struggled mightily Sunday afternoon (Irwin, the 54-hole leader, shot a final-round 79 and fell out of the top five).

Sullivan, who tuned pro shortly after his lone season at Florida in 1974, caught the Sunday woes, too. An eventual three-time winner on TOUR, Sullivan entered Sunday tied for 10th place at 3-over par. A 77 dropped him into a tie for 25th.

“As the week progresses and you get to the final day, you don’t want for it to matter more, but it’s hard to get that in your mind,” Sullivan said. “Because of the conditions, because of what you’re playing for, everything seems to be magnified. If you make a mistake, it seems like it’s a bigger mistake. The golf course is just so unforgiving.”

Norman’s 45-foot par putt on the 72nd hole got him into an 18-hole Monday playoff with Zoeller. A double bogey on No. 2 created a three-shot swing (Zoeller opened with consecutive birdies) and effectively ended Norman’s title hopes. Zoeller’s playoff-winning 3-under par 67 gave him the two lowest rounds of the week.

The very next year at Oakland Hills, North rebounded from the disappointing missed cut at Winged Foot and captured his second U.S. Open title. A divine bunker save on the tournament’s penultimate hole put North in rarefied air, linking him forever with legends like Bobby Jones, Walter Hagen, Ben Hogan, and Nicklaus as two-time U.S. Open winners.

“I was proud of that (save on 17). I'd spent probably an hour on that green practicing one of the evenings,” North said. "It had a huge ridge that ran through the middle of the green from back to front. It was probably four feet high. If the pin was on the right side and you were on the left side, you had absolutely no chance. You couldn't two-putt. I spent probably an hour on that green trying to hit chip shots and putts, trying to figure out how best to play that hole.

“I really felt like I could’ve won a bunch more tournaments,” North continued. “After ’85, between knees, back, elbows, I had a ton of surgeries and never really played a healthy year. I had a surgery every year from ’86 through ’93.”

North joined ESPN at the end of the 1992 PGA TOUR season, and, like Koch, returned to Winged Foot as part of the 2006 U.S. Open’s television coverage.

The field featured four Gators – 1989 Open Championship winner Mark Calcavecchia, 2005 Masters runner-up Chris DiMarco, an up-and-coming Camilo Villegas, and Horschel, a freshman who posted a top-10 finish at the NCAA Championship two weeks prior.

Only Villegas made the cut.

“I don’t know if there’s a course that really compares to this,” Horschel said of his experience at Winged Foot. “There’s no easy shot. There’s never a hole where you can catch your breath.”

Casual golf fans are undoubtedly familiar with how the most recent trip to Winged Foot ended.

Phil Mickelson took a one-shot lead to Revelations, the appropriately-named 18th hole. An errant drive and a pair of disastrous recovery attempts led to Mickelson’s dreadful double bogey. Relatively unknown Australian Geoff Ogilvy won the championship at 5-over par; he was the first over-par U.S. Open winner since North in 1978.

Mickelson’s meltdown will forever be the defining moment of the 2006 U.S. Open, but one of the aforementioned Gators always thought another contender’s collapse was far worse.

DeForest spent time on the European Tour before his career as a club professional began in 1989. Funny enough, DeForest turned down an assistant pro position at Winged Foot, opting instead for an opening at Roundout Golf Club in Accord, N.Y., where he worked for 28 years.

Colin Montgomerie was the European circuit’s rising star when DeForest played overseas.

By the time Montgomerie reached the 18th tee at Winged Foot, the 42-year-old Scotsman was a 30-time winner on the European Tour with four runner-up finishes in major championships. Two groups ahead of Mickelson, tied for the lead at 4-over par, Montgomerie put his drive in the fairway and was 171 yards from the flag.

Montgomerie’s 7-iron landed well short and settled in the greenside rough. Short-sided, Montgomerie flew his chip well beyond hole, then three-putted from roughly 30 feet for double bogey.

“If you know Colin Montgomerie… he doesn’t miss the green with a 7-iron once in 100 times,” DeForest said. “Everybody looks at Phil and says he lost it, but Montgomerie was sitting with it right there in his hands. He’s just one of those guys, if he’s got a 7-iron, he’s just not missing the green.”

Both Gators in the field this week are longshots to win, but they are playing outstanding golf.

Horschel was one of 30 players who made this year’s TOUR Championship, the final event of the FedEx Cup Playoffs.

Castillo (pictured below), the 2020 NCAA Division I Phil Mickelson Outstanding Freshman Award winner, is a beneficiary of the USGA’s decision to eliminate local and sectional qualifying this year due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Castillo’s exemption is a product of being second in last month’s World Amateur Golf Rankings. The Californian most recently made the semifinals of July’s Western Amateur, a prestigious tournament comprised of the world’s top amateur golfers.

A third Gators alum, Sam Horsfield, qualified with a pair of wins during the European Tour’s UK Swing, a traditional pathway to the U.S. Open for the circuit’s best players. The 23-year-old Englishman withdrew after a positive COVID-19 test Monday.

A few Gators from the previous trips to Winged Foot hope Castillo, Horschel, and the rest of the field run into rough similar to the U.S. Opens of their era. Mostly out of curiosity, given the drastic upgrades in technology.

Green, on the other hand, has no interest in seeing such a thing.

“In our day, the rough was comical,” said Green, a five-time winner on the PGA TOUR after his three seasons at Florida in the late 1970s. “If you hit it in the rough, there was not even an option to go at the green. They’ve since cut back on the rough, so you’ll see guys going for it, which I don’t mind because it actually brings double bogey into play. You’re risking getting it on the green, and you wind up with a worse lie, or hit a terrible shot because you’re trying to swing hard and get it out of the rough. Those variables come into play.”

Where exactly will the tournament be won and lost this week? North has a pretty good idea.

“You start looking at the back nine, there aren’t a whole lot of easy holes,” North said. “When you start making bogeys like they’re pars, that’s when you get in a lot of trouble.”

With NBC reacquiring live broadcast rights for the U.S. Open earlier this summer, not long after the tournament was scheduled to make its annual Father’s Day weekend conclusion, Koch will be back at Winged Foot.

He will call the action from a tower behind the 16th green all week. Just like 2006. And just like the previous U.S. Opens at Winged Foot, it would be quite surprising if anyone is under par by the time they reach him Sunday afternoon.

For Koch and the rest of the self-described “old guys” who love vintage U.S. Open golf, this week will certainly be better than most.

Take a flyover tour of Winged Foot's West Course: